May 12th, 2009

Articulations of the Dragon: Bruce Lee and Transnational Identity

* * *

Absorb what is useful, discard what is useless, add what is uniquely your own.

— Bruce Lee

On November 27th, 2005, a monument in honor of Bruce Lee was erected at the Avenue of Stars, a Hong Kong tourist attraction located at the Tsimshatsui Promenade along the Victoria Harbor waterfront. Modeled after the Hollywood Walk of Fame and created, according to its official website, “to pay tribute to outstanding professionals of [the] Hong Kong’s film industry, to promote [the] tourism industry, and to consolidate Hong Kong’s position as Asia’s World City,” the Avenue of Stars was, quite possibly, the ideal location to unveil a 2.5-meter tall, 600 kg bronze statue honoring the industry’s all-time biggest star. The inscription at the base of the statue says it all: “Bruce Lee: Star of the Century.” The tribute, however, was a long time in coming. When repeated attempts to urge the government to find a way to pay homage to Bruce Lee stalled, members of the locally based Bruce Lee Club took it upon themselves to raise upwards of US $100,000 to commission a sculpture. This long-awaited tribute finally occurred on what would have been the martial arts superstar’s 65th birthday had he not died in 1973. The fact that it took over thirty years to create a public monument in honor of Bruce Lee in Hong Kong is—to say the least—peculiar, considering the actor’s enduring fame. What is perhaps even more peculiar is that another country had already beaten Hong Kong to it—and in Bosnia and Herzegovina, no less.

Only a day before the unveiling of the statue in Hong Kong, the city of Mostar in Bosnia and Herzegovina unveiled a similar statue of Bruce Lee, making it the first public monument in the world to the international icon. This gold-plated bronze statue captures Lee in a familiar action pose –left arm raised with his palm facing outward, while his right hand grips his signature weapon, a pair of nunchaku.

At first glance, a Bruce Lee statue in Hong Kong makes a bit more sense than it does in Mostar. After all, the ethnically Chinese Bruce Lee was raised in Hong Kong and found international superstardom via the local film industry. Bruce Lee’s rooted and routed connection to Hong Kong is well-documented, but the actor has no evident tie to Bosnia and Herzegovina. What, then, was the rationale behind the Mostar officials’ seemingly incongruous choice of Bruce Lee as a local icon? The city was ravaged by bitter, bloody conflicts amongst rival ethnic factions during the Bosnian War of 1992-1995. According to Alexander Zaitchik, the creators of the monument viewed it as a “sly rebuke to the ongoing use of public spaces to glorify the country’s competing nationalisms.” Bruce Lee, then, was chosen as a symbol of solidarity meant to cross these divisive ethnic borderlands. “We will always be Muslims, Serbs or Croats,” one of the organizers remarked to the BBC, “But one thing we all have in common is Bruce Lee.”

This statement—absurd to some, perhaps inspiring to others—confirms much of what Jachinson Chan has already said about the world famous martial artist in his 2001 book, Chinese American Masculinities: From Fu Manchu to Bruce Lee. He writes, “Bruce Lee’s popularity crosses cultural boundaries in terms of race, class, gender, sexuality, and nationality. He was an international hero” (74). And he still is, if the statue in Mostar is any indication. Bruce Lee, the man, may have been snuffed out in the prime of his life, but his image, if not his “spirit” endures. In Hong Kong alone, numerous pretenders-to-the-throne with stage names like Bruce Le, Bruce Li, and Dragon Lee sought to fill the void in the wake of Lee’s death, starring in dozens of unofficial sequels, heartfelt homages, and crass attempts to cash-in on Lee’s popularity, each bearing titles like Exit the Dragon, Enter the Tiger (1976), Clones of Bruce Lee (1977), and Bruce Lee Fights back from the Grave (1976). So prolific were these films that many casual viewers who believe they have seen a Bruce Lee film in their lifetime may likely have only seen one of these pale imitations. Lee’s “absent presence” even had a strong affect on his contemporaries and successors. Even future superstar Jackie Chan found himself pressured in his early films to imitate Lee’s persona before finding his niche as a more comedic, Buster Keatonesque kung fu star. Further, Lee’s impact on martial arts cinema internationally was so dramatic that it would be impossible to elaborate upon it here. Despite being known for only a handful of films, Bruce Lee has gained enough recognition to be chosen as one of Time’s “100 Heroes and Icons of the Twentieth Century” alongside such figures as Che Guevara, Harvey Milk, and Mother Teresa. This recent honor speaks directly to the man’s prolific afterlife in the realm of cinema, DVDs, books, video games, t-shirts, posters, and numerous other cultural artifacts. As Stephan Hammond and Mike Wilkins write, “What Elvis Presley was to rock ‘n’ roll, Bruce Lee was to celluloid kung fu” (204). So popular is Bruce Lee that one need not to have ever seen a Bruce Lee film to be familiar with who he is.

In the succeeding paragraphs, I will examine Bruce Lee—the man, the myth, the legend—through the prism of articulation and multi-accentuality. Why would a city in Bosnia and Herzegovina erect a statue of Bruce Lee? And how does it differ from the reasons for having one in Hong Kong? Does it differ at all? In other words, how could a national and ethnic icon for one group be a post-national and post-ethnic icon for others? In the essay, I will propose a way in which we can view these two monuments as direct evidence of Bruce Lee as an articulated and multi-accentual cultural figure.

Learning from Bruce Lee

Even before learning about these two seemingly contradictory statues, I was already interested in writing Bruce Lee. The impetus for this a project was Meaghan Morris’s essay, “Learning from Bruce Lee: Pedagogy and Political Correctness in Martial Arts Cinema,” published in 2007’s The Worlding Project. Bruce Lee, naturally, is the spectral subject of Morris’s close-reading of two more-or-less unrelated, but still linked martial arts films: Hong Kong director Corey Yuen Kwai’s first English language film, No Retreat, No Surrender (1985), and American filmmaker Rob Cohen’s debut feature, Dragon: The Bruce Lee Story (1993). Both feature Bruce Lee as a character: in the former Lee serves as the mentor for the film’s protagonist, while in the other, he is, as the title suggests, the protagonist in this mostly biographical film.

Morris’s analysis of No Retreat, No Surrender (currently unavailable on Region 1 DVD) examines the film’s construction of Bruce Lee in a pedagogical role: he appears as a sage-like spirit (played by Korean-born Kim Tai-Chung) who guides the film’s underdog hero, an “alienated white boy” named Jason Stillwell. Of the film, she writes: “The film’s canny makers clearly understood Lee’s special role in US martial arts film culture: neither as a “body” nor a generic action hero, Lee is first and foremost an iconic film teacher” (47). Morris goes on to discuss the figure of the “trainer” in contemporary American cinema (1976’s Rocky) and connects it with a similar convention in Chinese films (1978’s 36th Chamber of Shaolin), eventually viewing No Retreat, No Surrender as a reworking of the Cold War-themes of Rocky IV by way of The Karate Kid, albeit with the more dynamic figure of Bruce Lee in place of the elderly Mr. Miyagi (Pat Morita).

But it’s something that arises during Morris’s close reading of a specific scene from Dragon: The Bruce Lee Story that really captured my attention, the one in which Bruce Lee (Jason Scott Lee) and future wife Linda Emery (Lauren Holly) attend a revival of Breakfast at Tiffany’s at a local Seattle theatre. Linda laughs heartily at Mickey Rooney’s bucktoothed, yellowface performance as Mr. Yunioshi, but instead of seeing her amusement mirrored in Bruce’s face, she turns to find him stone-faced: uncomfortable, if not outright furious. Recognizing the gap between her reaction and his, she identifies with Bruce’s perspective, and they leave the theatre together. Cue love scene.

If No Retreat, No Surrender is didacticism in action (the mentor-student relationship), then Dragon, Morris writes, is a lesson in how to read a film. What interests me most about her analysis is her characterization of Bruce Lee, the actual historical figure, in relation to the version presented in Rob Cohen’s film. Drawing on the work of Hong Kong cinema scholar Stephen Teo, Morris implies that the cinematic construction of an Asian American identity for Bruce Lee in Dragon is problematic, if not outright wrong since it runs counter to what we know about the purportedly nationalist and xenophobic tenor of Lee’s persona and films:

For some viewers, Dragon itself is a provocation to criticism; blurring Lee’s overt and distinctive cultural nationalism into a generalized “reaction against racism” (Teo 1997, p. 113), it transfigures a Hong Kong Chinese hero as flexibly “Asian”-American. Nowhere in the film is this effected more clearly than in the Breakfast at Tiffany’s scene, in which we watch a white American woman empathizing with a Chinese-American man identifying with a Japanese stereotype as embodied by an Irish-American actor. Now, as Teo (1997, p. 111) points out, Lee’s Hong Kong films were not only nationalist in an “abstract” way unrelated to a government or state (manifesting “an emotional wish among Chinese people living outside to China to identify with China and things Chinese”), they also had a “xenophobic streak” (p. 113)—in particular, towards Japanese. (53)

There are a number of different claims worth untangling in this passage, especially those involving Bruce Lee’s “overt and distinctive” cultural nationalism, the “xenophobic streak” of his films, and the “blurred” construction of an Asian American identity for Lee in Dragon: The Bruce Lee Story. In the face of Morris’s foreclosure of other articulations of Bruce Lee, I would first ask, to what degree are we talking about the appropriation of Bruce Lee – that is, the projection of a viewer’s (or a community of viewers’) desires, nationalistic or otherwise, onto Lee, and to what degree are we talking about the films he made, or better yet, the man himself? Shouldn’t we also take into account Bruce Lee’s personal history as well as his personal philosophy on the very subjects of race and nation before we accept such a proposition?

Perhaps in a preemptive strike against similar critiques of the quoted passage, Morris writes, “No doubt there is ample evidence of a ‘Western’ post-nationalist view of Lee” (53). Even so, she immediately buttresses this statement with Stephen Teo’s argument that a post-nationalist view of Lee is either false or, in his terms, only “what we want to hear” (we, presumably meaning Westerners in Teo’s formulation). The way Dragon aligns Lee with Asian American concerns seems to be symptomatic of a larger problem in Morris’s view: “I can’t help but see that a US identity politics, uninterested in any but American social conflicts and burdens, often ignores or refuses to imagine that things are different for people elsewhere” (53). Morris goes on to explain Lee’s appeal to Western audiences:

Lee’s modeling of an empowering cultural nationalism detached from any specific political state is exactly what makes him inspiring for the comparably abstract and culturalized ethnic “nationalisms” that flourish in the United States and other densely multicultural Western nations. (54)

The story that began this piece, involving the city of Mostar embracing Bruce Lee as a cultural touchstone may seem to confirm what Morris says about Lee’s inspirational, cross-cultural appeal to Western ethnic “nationalisms.” But it’s important to point out that Lee was not, in this case, a metaphorical conduit for a single ethnic nationalism, but a figure who was supposed to transcend several divergent ethnic factions within the city. Even the seemingly straightforward appropriation of a Chinese icon by Eastern Europeans is more complex than it seems. As Zaitchik points out, “Building civil society never seemed so weird: Here was a life-sized bronze statue of a topless American immigrant paid for by the German government and christened by a Chinese diplomat, erected at the behest of a dysfunctional community of Croats, Serbs, and Muslims.”*

And while he may indeed may be “all things to all men” in Teo’s phrasing, the underlying implication of both pieces is that only Western audiences have appropriated Lee to their own purposes, and in so doing, which intentionally or not, traffics in the assumption that Chinese audiences “get Bruce Lee” in ways that are, if not more authentic, then perhaps more correct than those pesky Westerners. That is to say, what goes unexamined and unchallenged here is the assumption that Bruce Lee is somehow a natural, totally unproblematic embodiment of an identifiably Chinese cultural nationalism. If there is a Western post-nationalist view of Lee, as Morris concedes, then how did such a view come into being? This question is something that both Teo and Morris quickly address, before effectively sweeping it under the proverbial rug. But it need not be.

To be fair, the portion of the Morris’s paper that I take issue with is but a small side note to her larger argument about Bruce Lee and his relation to film and pedagogy. And despite my occasionally polemical tone, I am not actually debating Morris or even Teo, but instead using their work as a springboard to explore Bruce Lee as an articulated and re-articulated (trans)national sign. Drawing on Stuart Hall, Laurence Grossberg, and V.N. Volosinov, I hope to investigate Bruce Lee’s iconic status as a specific point of articulation around which an extensive variety of cultural mythologies have been constructed—two of which I’ll be treating here.

While Lee may indeed by a figure that must be detached from any state-based cultural nationalism in order to be properly articulated for the delight and assorted purposes of audiences in the West, he is, in the same way, just as easily detached from certain post-national aspects of his persona in order to be attached to particular cultural, ethnic, or national identity politics from the East, if I may use an overly, and quite purposely simplified East-West binary. In other words, instead of viewing a film like Dragon: The Bruce Lee Story as a strategic American appropriation of Bruce Lee and the Chinese nationalist take as somehow self-evident or more valid, we should view them both as articulations— more naturalized than natural. Through a brisk examination of Bruce Lee’s short filmography as well as his culturally-complex life and personal philosophy, I will interrogate some of the popular assertions made by Morris and Teo and illuminate those areas elided by them as well, using articulation as a kind of theoretical framework to link Bruce Lee to larger transcultural phenomena.

Articulation and Multi-Accentuality

Why is articulation a useful way to analyze Bruce Lee? In my view, the language of articulation seems best suited to a discussion of Bruce Lee because it helps explain how a popular figure can validly be seen as, among other things, both nationalist and post-nationalist to different groups of people in different contexts. In the work of Stuart Hall and Laurence Grossberg, “articulation” isn’t just the act of “giving utterance or expression” in the common sense of the term, but instead a way of linking otherwise unrelated cultural forms, practices, and/or figures in significant ways. In the interview “On Postmodernism and Articulation,” Hall uses a big rig 18-wheeler, called an “articulated lorry” in England, as the point of reference for this term:

A lorry where the front (cab) and back (trailer) can, but need not necessarily, be connected to one another. The two parts are connected to each other, but through a specific linkage, that can be broken. The form of the connection that can make a unity of two different elements, under certain conditions. It is a linkage which is not necessary, determined, absolute and essential for all time.

In that sense, articulation can naturalize linkages and make them seem absolute when, in fact, they remain impermanent and subject to continual negotiation, translation, and adaptation. Grossberg describes it thusly:

Articulation is the construction of one set of relations out of another; it often involves delinking and disarticulating connections in order to link or rearticulate others. Articulation is a continuous struggle to reposition practices within a shifting field of forces, to redefine the possibilities of life by redefining the field of relations – the context – within which a practice is located. (54, emphases mine)

And so, a point of articulation is a specific site on the cultural landscape (an individual in the case of Bruce Lee) that serves as the primary channel by which two or more additional elements come to be articulated to one another, even mutually incompatible ones – in our case, the nationalistic and post-nationalistic discourses of identity attached to Bruce Lee. As such, the singling out Bruce Lee as a representative of cultural nationalism is an articulation, one that requires a de-articulation of many other facts.

If articulation is one word useful to such a discussion, multi-accentuality is another. Simply put, Bruce Lee serves as a multi-accentual sign, that is—he is a kind of that can be made to mean in many different ways. To borrow from John Storey’s work on the multi-accentuality of texts, Bruce Lee, then, can be articulated with different ‘accents’ by different people in different contexts for different politics” (4). This notion of multi-accentuality can be traced back to Russian critic V.N. Voloŝinov. In Marxism and the Philosophy of Language (1929), he writes:

Every sign, as we know, is a construct between socially organized persons in the process of their interaction. Therefore, the forms of signs are conditioned above all by the social organization of the participants involved and also by the immediate conditions of their interaction. When these forms change, so does sign. (21, emphasis his)

Multi-accentuality is reminiscent of Mikhail Bakhtin’s heteroglossia, which is defined in the glossary of The Dialogic Imagination as “a set of conditions—social, historical, meteorological, physiological—that will insure that a word uttered in that place and at that time will have a meaning different than it would have under any other conditions” (428). However, in this intersection of articulation, multi-accentuality, and heteroglossia, it’s important to explain what isn’t occurring here. In Elvis After Elvis: The Posthumous Career of a Living Legend, Gilbert B. Rodman does with the king of rock n’ roll what I’m attempting to do with Bruce Lee. At one point, he writes, “This isn’t to say, however, that Elvis is somehow an ‘empty signifier’ that can mean absolutely anything at all” (40). As with Rodman’s estimation of Elvis, I, too, should clarify that I am not saying articulation and multi-accentuality are just fancy ways of saying that Bruce Lee is more-or-less a cultural Rorschach test in which viewers see whatever they wish. If he was, there would be little point in writing about him or any other cultural phenomena for that matter.This isn’t how articulation and multi-accentuality work.

We have no direct access to the “real Bruce Lee.” What we do have are the cultural artifacts he left behind: interviews, letters, anecdotes from his friends and family. But the primary avenue through which many critics and viewers gain access to Bruce Lee is through his films.

Since Morris’s criticism of Dragon: The Bruce Lee Story actually comes from Stephen Teo’s Hong Kong Cinema: The Extra Dimensions, I will turn my attention there. In a chapter entitled “Bruce Lee: Narcissus and the Little Dragon,” Teo writes:

There is a decidedly ironic side to his success in the West, since an anti-Western sentiment is more than apparent in his persona. In his short career, Bruce Lee stood for something that in the 90s is hardly deemed politically correct: Chinese nationalism as a way of feeling pride in one’s identity.” (110).

It’s unclear whether he distinguishes between Bruce Lee’s onscreen and offspring personas, and even then, I’m not entirely convinced that Lee in any way embodied an “apparent” anti-Western sentiment in either—to consider oneself Chinese and to be proud of that fact does not necessarily make one anti-Western. Even so, Teo tends to homogenize Lee into a single figure. What I’m interested in doing here is parsing out the differences between his films and his life while at the same time pointing out that those seemingly stable categories are fraught with complexities and contradictions.

First, it seems a foregone conclusion in Morris’s and Teo’s estimation that Lee’s films are not just nationalist, but outright xenophobic, particularly against the Japanese. What I want to suggest that even if we could call these films nationalist or xenophobic (and I’m not sure we could in every case), it is more important to recognize not only the way in which these films deconstruct themselves, but also the way in which what occurs behind-the-scenes is perhaps just as important as what occurs on-screen. Further, I think it’s also important to point out that when most critics discuss Bruce Lee’s films, they rarely speak of the twenty or so films he did as a child in Hong Kong (most are unavailable in the West) or the bit parts in American movies like Marlowe with James Garner. What they are referring to are a handful of films produced between 1971 and 1973: The Big Boss, Fist of Fury, Way of the Dragon, and Enter the Dragon.**Since this is where nationalist and xenophobic articulations of Bruce Lee reside, these are the only films*** I will address.

The Big Boss

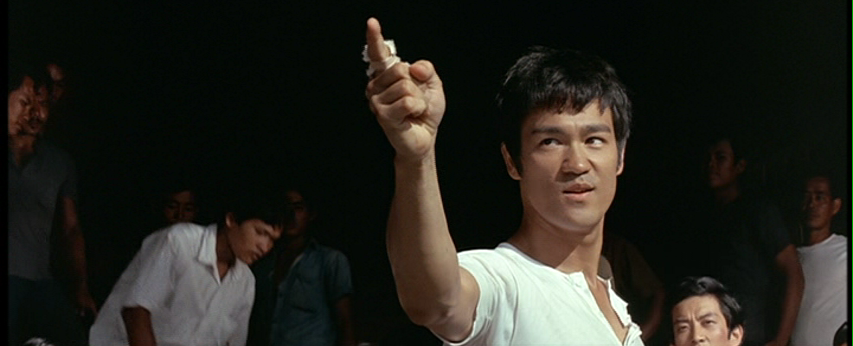

Riding high on the overseas success of the cancelled Green Hornet television series (re-titled “The Kato Show” in Hong Kong), Bruce Lee was finally given his big break by Golden Harvest head honcho Raymond Chow. After outbidding the Shaw Brothers for the actor’s services, the famous producer cast the promising young Lee in the 1971 production, The Big Boss. No one, including Bruce Lee himself, could have predicted the film’s massive success. Known to most American fans as Fists of Fury, this Lo Wei-directed film centers on a young, “fresh off the boat” brawler named Cheng Chow-An (Bruce Lee), who has just moved to Thailand. For Cheng, the change of scenery from Guandong seems to have less to do with bonding with his expatriate cousins, and more to do with staying out of trouble. We learn early in the film that Cheng has promised his aging mother that his fighting days are through. With the help of his cousins, he gets a job at a local ice factory.

Things go relatively smoothly until several of Cheng’s coworkers mysteriously disappear. Unbeknownst to our hero, the ice factory is really just a cover for illegal drug trafficking. Even worse, all of Cheng’s pals have been murdered. When Cheng’s cousin Hsu Chien (James Tien) goes missing, tensions flare at the ice factory, and it isn’t long before a fight breaks out between the workers and management. With his pals bullied beyond reason, Cheng finds he has no other choice but to fight. Recognizing Cheng as a viable threat to his emerging dope enterprise, Hsiao Mi—the “big boss” of the title—chooses to make him an unwitting ally. In a clever move, Hsiao Mi promotes Cheng from low-level grunt to foreman and even tempts him with an assortment of vices, namely, alcohol and women. Needless to say, Cheng’s sudden, all-too-chummy relationship with the big boss man alienates both his family members and his coworkers. Once Cheng’s staunchest supporters, they now see him as nothing more than a traitor. Things quickly take a turn for the worse, resulting in some major casualties and the abduction of Cheng’s innocent cousin, Chiao Mei (Maria Yi). As with most martial arts films of this type, a final fight is inevitable.

Is The Big Boss nationalist or xenophobic? My plot summary suggests as much with the Chinese abroad storyline, the Thai setting, and the exploitation of Chinese workers. And yet, it’s important to note that the villains aren’t Thai at all; they’re Chinese. As Jachinson Chan points out, “It is the Chinese capitalist who exploits and murders the Chinese communal workers, providing audiences with conflicting points of identification” (81). Can a film be xenophobic if there is no threat of foreign invasion, no slurs against foreigners, and the principal villains aren’t foreigners, but fellow citizens?

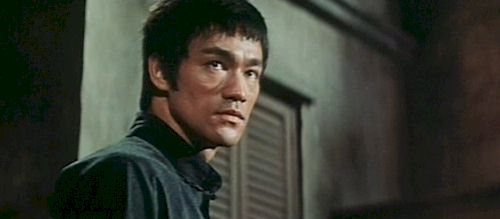

Fist of Fury

Though The Big Boss was a huge success for Bruce Lee in 1971, it was the 1972 follow-up Fist of Fury that truly catapulted him to the level of superstar. Known until recently in the United States as The Chinese Connection, this Lo Wei-directed flick spawned unofficial sequels, remakes, and numerous tributes after Lee’s death and rivals Enter the Dragon as Bruce Lee’s most well-known and well-loved films. In his only period film as an adult, Lee plays Chen Zhen, a young student from the Jing Wu school who returns home to find his venerable sifu dead—most likely the victim of the treacherous rival Japanese dojo. Set sometime in the early twentieth century during the occupation of Shanghai by Japan, the film depicts the violent Sino-Japanese tensions of the time.

Perhaps the only unabashedly nationalistic film Bruce Lee ever appeared, Fist of Fury demonstrates a clear bias against the Japanese, all of whom resemble nasty caricatures seemingly pulled straight from American World War II propaganda. In one scene designed to rouse Chinese audiences, Chen Zhen roundly defeats an entire dojo of Japanese fighters and declares, “We are not sick men!” a direct reference to the derogatory epithet “Sick Man of Asia” used by the Japanese against the Chinese during this era. Another standout scene is Chen Zhen’s meltdown at the public park in which he is denied entry by a security guard. Provoked by discrimination and a sign that reads “No Dogs and Chinese Allowed,” Chen Zhen dispenses a bunch of Japanese thugs with brutal efficiency just before he kicks the sign into pieces.

I would concede that the film is undeniably pro-Chinese, anti-imperialist, and xenophobic in varying degrees, but given the historical context, it’s not unexpected. What interests me here is how this film serves the focal point for which a nationalist/xenophobic view of Bruce Lee can be articulated. None of Bruce Lee’s other films feature Japanese stereotypes, although Morris suggests that they do. And it’s worth noting that Bruce Lee did not write or direct this film. He had no creative control; he was a work-for-hire actor. In fact, he reportedly had a falling out with the director Lo Wei over the film’s racial content. Certainly, the film makes a folk hero out of the fictional Chen Zhen, but at the same time, it undermines him—many of his fellow students would still be alive if not for his proto-slasher movie antics in investigating his master’s death. In that sense, even a film with a seemingly straightforward nationalist project has its complexities.

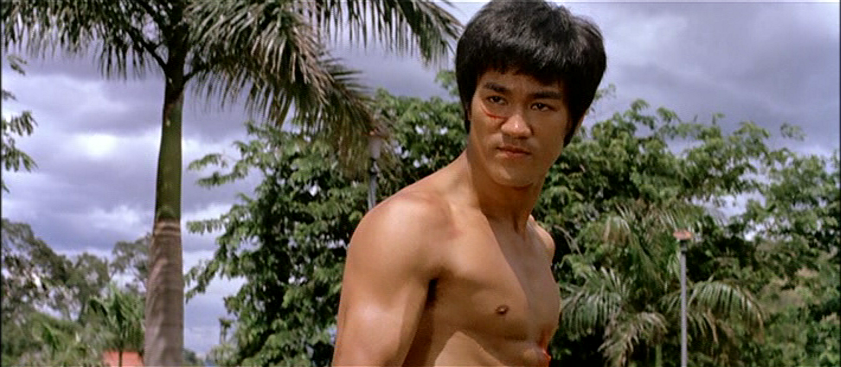

Way of the Dragon

In 1972’s Way of the Dragon, Lee stars as Tang Lung, the Hong Kong equivalent of a backwater hick, who is plopped down in the middle of bustling Italy. In a departure from his two previous HK roles, Lee is not all business this time around: he smiles, jokes, laughs, and generally mugs for the camera when he’s not dealing out some martial justice. The plot centers on his frequent run-ins with some local thugs who are muscling in on his uncle’s Chinese restaurant. If the film is considered by some to be anti-Western, then perhaps it’s because of the Italian setting and the use of Chuck Norris as one of the primary villains. And yet, as the film seems to construct these East vs. West binaries, it’s notable how Lee, who directed and wrote the film, worked his own personal philosophy of the martial arts during the battle. Tang Lung only begins to beat the American fighter (Norris) when he abandons his strictly Chinese style of fighting for something more effective, a perfect example of Bruce Lee’s adopted precept, “Absorb what is useful, discard what is useless, and add what is uniquely your own.”

And I have to admit, however, I find Stephen Teo’s critique of Lee’s performance to be perplexing. He writes:

Lee’s indulgence in playing the bumpkin does not stand him in good stead with Western critics who will be put off by the grossness and crass naivety of his character, because it strikes so close to home. This bumpkin easily reminds Westerners of the infamously rude Chinese waiters in Chinese restaurants all over Europe. (116)

Leaving aside Lee’s (de)merits as an actor, I would actually argue the opposite. I cannot speak for European audiences, but the bumpkin persona actually makes Lee more relatable in the way that it so easily articulates with a whole set of positive cultural figures in literature, stage, and screen that are immediately recognizable to Americans, including any number of “innocent abroad” and “fish out of water” tales.

Enter the Dragon

Robert Clouse’s 1973 worldwide hit Enter the Dragon is a landmark film for a number of reasons. For starters, not only did the movie help introduce American audiences to the martial arts film genre, but it also propelled Bruce Lee to international superstardom, albeit posthumously. Plot-wise, Enter the Dragon plays out like a kung fu-heavy James Bond flick. Bruce Lee plays a Shaolin monk un-creatively named Lee who’s called upon by British intelligence to infiltrate the island of an evil Chinese druglord named Han (Shih Kien) by competing in the villain’s martial arts tournament. Along the way, Lee meets some American friends: conman extraordinaire Roper (John Saxon) and funk soul brother Williams (Jim Kelly), but as is the case with all the James Bond movies, our protagonist must uncover and thwart the arch-villain’s devious plot all by his lonesome before finally calling for reinforcements. Though the film’s representation of Chinese culture is a little too Hollywood, its depiction of Bruce Lee’s martial arts philosophy is right on the money. From Lee’s refusal to wear a uniform to his clever “art of fighting without fighting,” Enter the Dragon showcases tenets of Lee’s martial arts outlook in a more pronounced way than his previous effort, Way of the Dragon, did. The refusal to wear a traditional uniform is something that Lee would have expanded on in The Game of Death had he not died before it was completed. In the footage he shot, Lee wears a yellow jumpsuit, while the villains where traditional Japanese, Chinese, and Korean garb. The choice was to suggest that Lee had no allegiance to any one style, and this, in part, is how the post-nationalist articulations of Lee have come into being.

The Man Himself

The suggestion that Dragon: The Bruce Lee Story erroneously constructs an Asian American identity for the “Hong Kong Chinese hero” is compelling, but one can’t help but ask, “Doesn’t construction (or appropriation) go both ways?” Certainly, Morris’s analysis of No Retreat, No Surrender supports such a vision, but if we really want to consider racial and national boundaries, Bruce Lee is by all means an atypical “Hong Kong Chinese hero.”

Bruce Lee was born on November 27th, 1940 at the Chinese Hospital in San Francisco’s Chinatown. His father, a visiting actor named Lee Hoi-Chuen, was Chinese, while his Catholic mother, Grace, was of Chinese and German descent. His real name was Lee Jun-Fan (“to arouse and shake the foreign countries”), but it was reportedly the supervising doctor, Mary Glover, who suggested his English name for the hospital records (Yang 54). Although he returned to Hong Kong three months later, he was a citizen of the United States by birth and never became a Hong Kong citizen. After living in Hong Kong, he completed his high school education in Seattle, going on to study drama and philosophy at the University of Washington where he met his wife, Linda Emery, herself of English and Swedish descent. Less than a year after getting married, she bore him a son, Brandon and, in 1969, they had a daughter, Shannon. This is a summary of Lee’s life before he became famous and already one can see how everything is already articulated – neither “purely” Chinese nor American, as if these cultures were ever “pure.” As Jachinson Chan states:

Lee’s birth in America is significant because it legitimizes his Chinese American identity in he form of citizenship. Technically speaking, Lee is a second-generation Chinese American, caught in a conflictual cultural predicament where he is an American citizen, entitled to the social and legal benefits of a capitalist democratic system, yet simultaneously a minority who faces racism, stereotypes, and cultural exclusion from the dominant/mainstream culture, particularly in the television and film industries. Lee’s experiences are common among many Asians in America who are Americans by birth and yet are treated as perpetual foreigners. (75)

I don’t mean to use this quote to affirm that Bruce Lee was Asian American; I only cite it and a shortened biography to suggest how complex and contradictory his life was. To say that Bruce Lee’s persona, as Teo and Morris do, represents a cultural nationalism means one has to simply ignore certain details through disarticulation. On a similar note, to construct Bruce Lee as a post-nationalist cultural figure, also means one has to ignore certain details of his life that contradict that belief.

In a collection of interviews called Words of the Dragon, editor John Little includes a Taiwanese newspaper article entitled “Me and Jeet Kune Do” in which Bruce Lee writes, “A Chinese is, and always will be, a Chinese; I am a Chinese, I had better shoot Chinese films!” (130). Little dismisses this as too nationalistic and perhaps manufactured by the Taiwanese paper. In response, he cites Bruce Lee: The Lost Interview (1971). Upon being asked whether he thought of himself as Chinese or American, Lee responds, “You know what I want to think of myself? As a human being. Because, I mean I don’t want to be like ‘As Confucius say,’ but under the sky, under the heavens there is but one family. It just so happens that people are different.” But as much as I like this quote for my own reasons, to what degree can we view both those responses as the direct results of the contexts in which they were given – one to a Chinese audience, the other to an American one? Bruce may indeed be telling one audience what they want to hear or perhaps both, but there is no way to be sure. And it is in that uncertainty that these two mutually incompatible articulations come into direct contact.

The Always Articulating Dragon

Perhaps Bruce Lee is Chinese in the way Tiger Woods or Barack Obama are black – self-identification may be important, but identity can also hinge on which community is willing to claim you as a member and how others outside the community view you. Sometimes these identifications align, sometimes they multiply. In this piece, I am not looking for the “real” Bruce Lee nor am I concerned with notions of authenticity. Instead I am trying to suggest that Lee is already a more complicated figure long before any viewer – Eastern or Western – gets his or her hands on him.

None of this actually explains why Bruce Lee endures though. Strangely, it might be Voloŝinov who has the answer. He writes:

This social multiaccentuality of the ideological sign is a very crucial aspect. By and large, it is thanks to this intersecting of accents that assign maintains its vitality and dynamism and the capacity for further development. A sign that has been withdrawn from the pressures of the social struggle—which, so to speak, crosses beyond the pale of the class struggle—inevitably loses force, degenerating into allegory and becoming the object not of live social intelligibility but of philological comprehension. (23)

Nationalism and post-nationalism are but two of the interacting accents when it comes to Lee. His martial artistry is one; his death looms large as another. Though the official cause of Lee’s death was listed as cerebral edema caused by an allergic reaction to the painkiller Equagesic, the mystery surrounding his passing has endured to this day with numerous conspiracy theories abounding. To compound matters, Lee’s son Brandon was tragically killed on the set of The Crow, a film that could have made him a star had he lived. This bizarre accident only further added credence to stories of a so-called “Curse of the Dragon.” Whatever the truth, Lee’s obvious charisma, groundbreaking films, and widely-recognized talent, coupled with his untimely death have vaulted his life story to the stuff of myth and legend, spawning a legion of devotees and countless imitators. So in that sense, the Dragon may never die.

I began with a story of monuments; I will end with another. In 2007, students at the University of Washington made attempts to have a statue of Bruce Lee erected. “I’m not for taking any of the existing statues down,” organizer Jamil Suleman told the Seattle Times, referring to the memorials of white males on campus. “I’m just for putting up statues that represent us.” After close to a year of trying and ultimately failing to persuade the UW Regents to create a statue in honor of Lee, a student group called “The Bruce Lee Project” recently petitioned for a reflective garden in his name to be located in front of the Husky Union Building. “What we are trying to do with this peace garden,” Suleiman explains, “is have a space that anyone on campus can feel they belong in.”

____________________________________

* Further, what do we make of the irony that a figure of peace, as the Bruce Lee statue was intended to be, would be depicted carrying a weapon, one that has been outlawed in many countries and has even been considered so dangerous that, until recently, it was consistently edited out of films by the British censors? In addition, the weapon’s relation to Bruce Lee is itself an articulation. One might be tempted to think that Lee himself created them when in fact, it was Japanese invention (via Okinawa by way of China).

**The Game of Death (1979) was completed posthumously with the use of Bruce Lee lookalikes and recycled footage. The film contains less than fifteen minutes of new footage of Bruce Lee.

***The bulk of my film summaries come from my film reviews at LoveHKFilm.com.

Bibliography:

Bakhtin, M.M. The Dialogic Imagination. Ed. Michael Holquist. Trans. Caryl Emerson and Michael Holquist. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 1981

Chan, Jachinson. Chinese American Masculinities: From Fu Manchu to Bruce Lee. New York: Routledge, 2001.

Grossberg, Laurence. We Gotta Get out of this Place: Popular Conservatism and Postmodern Culture. New York: Routledge. 1992

Hall, Stuart. “On Postmodernism and Articulation: An Interview with Stuart Hall.” Journal of Communication Inquiry 1986 10: 45-60.

Hammond, Stefan and Mike Wilkins. Sex and Zen; A Bullet in the Head: The Essential Guide to Hong Kong’s Mind-Bending Films.New York: Fireside Press, 1996.

Lee Bruce. Words of the Dragon: Interviews, 1958-1973. ed. John Little. Boston: Tuttle Publishing, 1997.

Morris, Meaghan. “Learning from Bruce Lee: Pedagogy and Political Correctness in Martial Arts Cinema.” The Worlding Project. Eds. Christopher Connery and Rob Wilson. Santa Cruz, CA: New Pacific Press, 2007

Storey, John. Cultural Studies and the Study of Popular Culture. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2003.

Teo, Stephen. Hong Kong Cinema: The Extra Dimensions. London: British Film Institute, 1997.

Yang, Jeff. Once Upon a Time in China. A Guide to Hong Kong, Taiwanese, and Mainland Chinese Cinema. New York: Atria Books 2003

Zaitchik, Alexander. “Mostar’s Little Dragon: How Bruce Lee Became a Symbol of Peace in the Balkans. Reason.com. April 2006. http://www.reason.com/news/show/33300.html

May 16th, 2009 at 5:16 am

Exelent article, makes us reflect on a man who has become as legendary as the dragon itself

May 22nd, 2009 at 5:31 pm

woah nice study there!

you will interested in the documentary from history tv

‘how bruce lee changed the world’.

on youtube..

May 29th, 2009 at 10:32 pm

TopDog…

I am So Lucky That I found your blog and great articles. I will come to your blog often for finding new great articles from your blog.I am adding your rss feed in my reader Thank you…

September 22nd, 2009 at 5:57 pm

Checked out the Bruce Lee documentary awhile back. Thanks!

Why is all the spam for this and only this post in Russian?

January 15th, 2010 at 12:53 pm

As a Mixed Martial Arts fighter I have nothing but respect for this man. I am 17 and still I recognize that this man is the reason martial arts is something studied by millions around the world. The fact he died in 1973 is a tragedy no matter what really happened. This man is an icon and deserves to be recognized as one. R.I.P Mr. Lee you are gone but you will never be forgotten

February 7th, 2010 at 10:44 pm

[…] I don’t think it’s any secret that I’m a fan of Bruce Lee. After all, I’ve reviewed all his major films for this website, came up with a short bio for his LoveHKFilm.com People Page, wrote a little article about some film and TV projects of his that never came to pass, and even penned a long-winded blog post about his transnational appeal. […]

March 19th, 2010 at 3:12 am

iam very very big fan of the legendry martial artist BRUCE LEE.i love him very much.his speed,intensity,power,intellegency,hard working was amazing.i hopefully thank you for giving the information.